Alabama Women’s Lives

Introduction

A vital way of making sense of the past is to look at personal accounts of the people who lived it. American women’s stories, unfortunately, have often been harder to capture than men’s. For much of modern history, their sphere was the home. Participating less in public life meant less of a public voice — and less of a public record. For women in minority groups, these voices and records were even more likely to be devalued or ignored.

Southern women’s lives are in particular danger of receding into the darkness. Their real experiences and personalities are easily overshadowed by their cultural portrayals, some faithful fictions and some outright caricatures, books from Gone with the Wind and Fried Green Tomatoes to The Color Purple and The Help; films from Steel Magnolias and Coal Miner’s Daughter to Beasts of the Southern Wild and Winter’s Bone; and television shows from Designing Women and Dallas to True Blood and Nashville. But what have Southern women actually understood their lives to be about?

What did they experience on the farm or in the city? How did they feel about owning slaves or being slaves? Were they true Confederates or did they feel like outsiders? How did they react to emancipation and Reconstruction, to electric light and the telephone, to industrialization and the right to vote? How did they live during the Great Depression, World War II, the Age of Aquarius? Where were they when they heard that President Kennedy had been shot, or Martin Luther King Jr? How did they feel when they saw the moon landing or the fall of the Berlin Wall? The questions are endless.

With so many collections focused on local people and places, the University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections is a good place to research the lives of Southern women, in particular those from Alabama. Every woman on the maps below has real ties to Alabama, having spent some significant portion of their lives in the state. They are spread out through dozens of collections, so they have been brought together here, so as to emphasize their depth and breadth and facilitate research.

Using This Portal

The Maps section presents various visualizations of all the women’s lives you can explore via The University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections. Click on each marker to bring up biographical information and content descriptions, and to find out how to access the associated archival materials, including links to any online finding aids or digitized items.

Women are listed by the name they used when they created the items discussed, with any later married names also included in brackets. In some cases, we don’t know much about the creator beyond what one can glean from the materials themselves, and we don’t always have time to explore them thoroughly. If your research into any of these women and their materials turns up data others might find helpful, please let us know!

The Glossary gives an overview of and commentary on the forms you will encounter when digging into these women’s lives. It also gives definitions of the various genres, some of which are familiar but others which may not be.

The Resources section provides a list for further reading. All items or collections are available via UA Libraries, and info about how to find them is given below.

- A list of Collections referenced on the map, including links to Finding Aids if they are online.

- A list of Secondary Sources for further research, books that address various aspects of Alabama, Southern, and American women’s history.

The About section lists the team of people involved in creating this portal and briefly describes how it all came together.

Maps

The maps below allow for different ways of discovering women to research, based on either the format of the materials in their collections or the historical era those materials reflect. In a few cases, a woman’s name will show up in multiple lists on the same map, because she generated materials in multiple formats or covering a fairly broad period of time. The Notes field should indicate this.

On either map, if you’d like to see a larger version, use the icon at the top right corner to launch the map in its own browser tab.

Glossary

About These Formats

While most forms included here were created at the time the events took place, some are retrospective. One such after-the-fact genre, the oral history, occasioned a rethinking of this project to include non-written sources. What retrospective reflections and narratives lose in the immediacy of detail and the freshness of the telling, they gain in big picture contextualization and interpretation. And they often cover a much broader period of time, allowing for discussions of long-term growth and development of the person and the society they lived in.

Most forms included here are also first person, that is to say, they are created by the woman who compiled them. Some, including the autograph book and the memory book, are second person; they record thoughts and feelings of others as addressed to the compiler. Most are in many ways third person objects, collecting the writings and thoughts of others who don’t even know their words and ideas have been cherished by someone else. In all cases, the motives and personality of the compiler are still central.

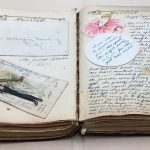

Most importantly, many of the items included here do not neatly fall into one genre or even two. In part, this is because genres are descriptions, not prescriptions, so they reflect the messiness of reality. Personal books are also subject to the motives and needs of the creator, needs that might be complex or change over time. One example is the scrapbook/diary of Mamie Kennedy Perkins. The left-hand pages are filled with programs from her musical performances in the 1870s and 1880s; the right-hand pages were filled with diary entries from the 1890s. Did she paste in those programs when the events happened, then return to the book for a different purpose? Or did she use empty facing pages in a diary to save cherished memories?

Definitions

Autograph book

A blank book used to capture signatures, messages, quotes, poetry, and other writings from friends and acquaintances, as well as drawings. Sometimes ephemera like calling cards or photos might be included.

Commonplace book

A personal anthology of aphorisms, short passages from literature, poems, and other notes transcribed into a blank volume to serve the memory or reference of the compiler (definition of commonplace book from Society of American Archivists). In the 19th century, women used the genre for poetry as well as recipes, both often clipped out of newspaper, such that it became a species of scrapbook. This practice fell out of favor in the early 20th century.

Diary

A document, usually bound, containing a personal record of the author’s experiences, attitudes, and observations (definition of diary from Society of American Archivists). Some of these books were made to be diaries, with pre-printed sections set aside for each day, while others are simply blank books or notebooks. They may include non-narrative elements, such as drawing or poetry. There are subtle disctinction between this format and a journal (see definition of journal from Society of American Archivists), but in our practice, the two terms are used relatively interchangeably.

Memory book

A pre-printed book designed to be filled in with specific information about one’s life and experiences. Most in our collections are early 20th century precursors to the high school yearbook, providing space for students to record info about the school and messages from friends, classmates, and teachers. It functions similarly to an autograph book in content and a scrapbook in format.

Oral history

An interview that records an individual’s personal recollections of the past and historical events (definition of oral history from Society of American Archivists). This genre is something like the spoken version of a memoir — with all that difference the medium entails, including less formality, no after-editing, and often the presence of another person or persons to ask questions or give prompts.

Scrapbook

A blank book, often with a simple string binding, used to store a variety of memorabilia, such as clippings, pictures, and photographs (definition of scrapbook from Society of American Archivists). The scrapbook is a wide-open genre incorporating any number of media. It is especially congenial to the assembly of ephemera and souvenirs, sometimes becoming less like a book and more like a treasure trove.

Travel journal

A contemporaneous or retrospective account of a trip or vacation, sometimes taking on the character of a scrapbook, with photos, maps, and memorabilia accompanying diary-style narrative and commentary.

Resources

The Collections

Listed numerically, by collection number. MSS numbers are found at Hoole Library; W numbers are from the Williams Americana Collection. Links are to the collection Finding Aid online, when available. For collections without an online Finding Aid, contact archives@ua.edu for more information.

Alan DeSantis Audio Cassettes (2012.041)

- Materials in this collection are subject to restrictions on their use. Contact archives@ua.edu for more information.

Archive of American Minority Cultures (MSS.0084)

- Note: The majority of this collection is not open to the public. The audio oral histories referenced on this page are an exception; they have been digitized and are available in our Digital Collections: Working Lives Oral History Project.

George and Eleanor Bridges Papers (MSS.0210)

Helen N. Butler scrapbook (MSS.0244)

John and Mary Wellborn Cochran Diaries, Letterbook, and Photographs (MSS.0326)

Sarah Ann (Gayle) and William B. Crawford Papers (MSS.0369)

Daphne Cunningham Diaries (MSS.0385)

Janie May Eppes papers (MSS.0489)

Julia Neely Finch Papers (MSS.0515)

Pauline Jones Gandrud papers (MSS.0555)

Garner Family scrapbook (MSS.0559)

Josiah and Amelia Gorgas Family Papers (MSS.0580)

Mrs. Oscar Hall scrapbook (MSS.0611)

Jefferson Franklin Jackson family papers (MSS.0736)

Keyes Family papers (MSS.0813)

Madolyn S. Lloyd scrapbook (MSS.0869)

Sara Mayfield papers (MSS.0935)

- Materials in this collection are subject to restrictions on their access and use. Contact archives@ua.edu for more information.

McCorvey-Tutwiler families papers (MSS.0947)

Earl McGowin papers (MSS.0955)

Ersie Walker Neeley diaries and papers (MSS.1039)

Perkins family papers (MSS.1127)

Aurulia Taylor autograph book (MSS.1385)

Augusta Evans Wilson papers (MSS.1563)

Fletcher and Jean Howington Family papers (MSS.1627)

Lorraine Standish papers (MSS.1636)

Meriwether Family Papers (MSS.2217)

Abby Hazard Snow Family Memorabilia (MSS.2604)

Kate H. Durr Scrapbook (MSS.3433)

Mary Rebecca Strudwick memory book (MSS.3633)

Verner family papers (MSS.3741)

Ruth Bealle Glass Memory Book and UA Athletic Association membership ticket (MSS.3868)

Annie Perkins commonplace book (MSS.3875)

Janette Goldstein Blum Scrapbook Collection (MSS.3913)

Edna Lee Holladay diary (MSS.4044)

Violet Rochelle Wolford diary (MSS.4065)

Mildred McCollum diary (MSS.4067)

Winifred Ruth O’Rear diaries (MSS.4133)

Mary Lucinda Smith commonplace book (MSS.4146)

Mary Elizabeth Streit Preston papers (MSS.4156)

Patti Julia Malone autograph album and papers (MSS.4169)

Cornelia Bolen commonplace book and photographs (MSS.4225)

Wade Hall collection of diaries and scrapbooks (MSS.4259)

Collection on women in Alabama (W.0005)

Aurora Pryor McClellan commonplace and autograph book (W.0015)

Marie Brink memory book, Sidney Lanier High School, 1922 (W.0017)

Virginia J. Hanson papers (W.0018)

Sarah Shorter Hunter commonplace book (W.0019)

Lola Higginbotham memory book, McAdory High School, McCalla, Alabama (W.0033)

Mary C. Kelly scrapbook (W.0036)

Jennie C. Lee papers (W.0113)

Harriett Anna Kennedy papers (W.0117)

Secondary Sources

Listed alphabetically. All are available in the UA Libraries collections, as noted with the call numbers below.

Appleton, Thomas H., and Angela Boswell, eds. 2003. Searching for their Places: Women in the South across Four Centuries. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. [Gorgas Library, Call Number HQ1438.S63 S42 2003]

Bernhard, Virginia. 1992. Southern Women: Histories and Identities. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. [Gorgas Library and Hoole Library (Alabama Coll.), Call Number HQ1438.A13 S623 1992]

Boucher, Ann. 1978. Alabama Women: Roles and Rebels. Troy, Ala.: Troy State University Press. [Hoole Library (Alabama Coll.), HQ1438.A2 B68]

Clayton, Bruce, and John A. Salmond. 2003. Lives Full of Struggle and Triumph: Southern Women, Their Institutions, and Their Communities. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Gorgas Library, Call Number HQ1438.S63 L58 2003]

Coryell, Janet L., ed. 1998. Beyond Image and Convention: Explorations in Southern Women’s History. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. [Gorgas Library, Call Number HQ1438.S63 B48 1998]

—–, ed. 2000. Negotiating Boundaries of Southern Womanhood: Dealing with the Powers That Be. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. [Gorgas Library, Call Number HQ1438.S63 N44 2000]

Fox-Genovese, Elizabeth. 1988. Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Gorgas Library and Hoole Library (Alabama Coll.), Call Number HQ1438.A13 F69 1988]

Gold, David, and Catherine Hobbs. 2014. Educating the New Southern Woman: Speech, Writing, and Race at the Public Women’s Colleges, 1884-1945. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [McLure Library, Call Number LA230.5.S6 G65 2013]

Harris-Perry, Melissa V. 2011. Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Gorgas Library, Call Number E185.86.H375 2011]

King, Wilma. The Essence of Liberty: Free Black Women during the Slave Era. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. [Gorgas, Call Number E185.18.K56 2006]

Murray, Gail Schmunk, ed. 2004. Throwing off the Cloak of Privilege: White Southern Women Activists in the Civil Rights Era. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Gorgas Library, Call Number E185.98.A1 T49 2004]

Rivers, Larry E., and Canter Brown. 2009. The Varieties of Women’s Experiences: Portraits of Southern Women in the Post-Civil War Century. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Gorgas Library, Call Number HQ1438.S63 V37 2009]

Schuyler, Lorraine Gates. 2006. The Weight of Their Votes: Southern Women and Political Leverage in the 1920s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Gorgas Library, Call Number HQ1236.5.S676 S38 2006; also available electronically]

Smith, Katy Simpson. 2013. We Have Raised All of You: Motherhood in the South, 1750-1835. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. [Gorgas Library, Call Number HQ759.S6185 2013]

Thomas, Mary Martha. 1995. Stepping out of the Shadows: Alabama Women, 1819-1990. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. [Gorgas Library and Hoole Library (Alabama Coll.), Call Number HQ1438.A2 S75 1995]

Walker, Melissa, Jeanette R. Dunn, and Joe P. Dunn, eds. 2003. Southern Women at the Millennium: A Historical Perspective. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. [Gorgas Library, HQ1438.S63 S68 2003]

White, Deborah Gray. 1999. Too Heavy a Load: Black Women in Defense of Themselves, 1894-1994. New York: Norton. [Gorgas Library, Call Number E185.86.W43875 1999]

About

This page was created by the University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections, with the helpful guidance of the Alabama Digital Humanities Center and UA Libraries Web Technologies and Development.

- (SC) – Project design, website content and implementation

- Tyler Grace (ADHC) – Project design, website implementation

- Emma Annette Wilson (ADHC) – Project coordination

- Steven Turner (WTD) – Website coordination

I believe in being transparent, especially when I think an understanding of my process might be helpful to others. If you would like to create a similar kind of data map, it mostly takes a lot of patience, not a lot of technical know-how.

I combed our archives database for items that fit the bill, then created a spreadsheet with metadata harvested or adapted from current finding aid data and/or created through additional examination and processing. But before I had collected more than a sample size of data, I consulted with Emma and Tyler, who helped me conceptualize the project (just what is this thing?) as well as think through how best to translate the data into a useful map.

Though we had planned to use Google Fusion Tables to generate the map, which would have involved some extraneous coding from Tyler to make the display behave as we wanted — notably, to render a lot of descriptive text as a sidebar flyout, rather than a pop-up — we found that Google My Maps could accomplish most of our goals without additional jiggery-pokery! My Maps provides a graphic interface through which you can upload structured data as an overlay and tailor the visualization to suit your needs. (Alternatively, you can create points and lines on a map from scratch within the interface.) It does have its limitations, though, so we created two separate maps, rather than attempt to deploy complex filtering within one.

Also worth noting is the question of where to house the project, and how best to organize it. Steven helped me determine that a one-page setup was the way to go, from a usability standpoint. Moreover, he drove me to think about the project in context, what part of the website it would live in and, more importantly, whether it might be the first of many such portals in need of a concerted online home.

Obviously, the final product would not be what it is without the thoughtful collaboration of those mentioned above and my colleagues in Special Collections.